For some reason, thinking of America, the money, the mess, the churches and the election, I kept thinking of this passage from the end of James Joyce's story Grace:

`For the children of this world are wiser in their generation than the children of light. Wherefore make unto yourselves friends out of the mammon of iniquity so that when you die they may receive you into everlasting dwellings.'

Father Purdon developed the text with resonant assurance. It was one of the most difficult texts in all the Scriptures, he said, to interpret properly. It was a text which might seem to the casual observer at variance with the lofty morality elsewhere preached by Jesus Christ. But, he told his hearers, the text had seemed to him specially adapted for the guidance of those whose lot it was to lead the life of the world and who yet wished to lead that life not in the manner of worldlings. It was a text for business men and professional men. Jesus Christ, with His divine understanding of every cranny of our human nature, understood that all men were not called to the religious life, that by far the vast majority were forced to live in the world, and, to a certain extent, for the world: and in this sentence He designed to give them a word of counsel, setting before them as exemplars in the religious life those very worshippers of Mammon who were of all men the least solicitous in matters religious.

He told his hearers that he was there that evening for no terrifying, no extravagant purpose; but as a man of the world speaking to his fellow-men. He came to speak to business men and he would speak to them in a business-like way. If he might use the metaphor, he said, he was their spiritual accountant; and he wished each and every one of his hearers to open his books, the books of his spiritual life, and see if they tallied accurately with conscience.

Jesus Christ was not a hard taskmaster. He understood our little failings, understood the weakness of our poor fallen nature, understood the temptations of this life. We might have had, we all had from time to time, our temptations: we might have, we all had, our failings. But one thing only, he said, he would ask of his hearers. And that was: to be straight and manly with God. If their accounts tallied in every point to say:

`Well, I have verified my accounts. I find all well.'

But if, as might happen, there were some discrepancies, to admit the truth, to be frank and say like a man:

`Well, I have looked into my accounts. I find this wrong and this wrong. But, with God's grace, I will rectify this and this. I will set right my accounts.'

For the past four years, whenever America has been on my mind, it has seemed like a question, a living, teeming question more than a nation: "What next?" A question, under strain from all sides, pushing and pulling itself towards a future nobody seems to have envisioned and everyone is sure they are a little afraid of.

Fear has been, at least from a distance, a very palpable undercurrent even in the last few weeks of the American elections. Fear of the economic situation. Fear of what happens. Fear of the wider world. Fear that jobs will be lost. Fear of McCain. Fear of Obama.

Fear for Obama.

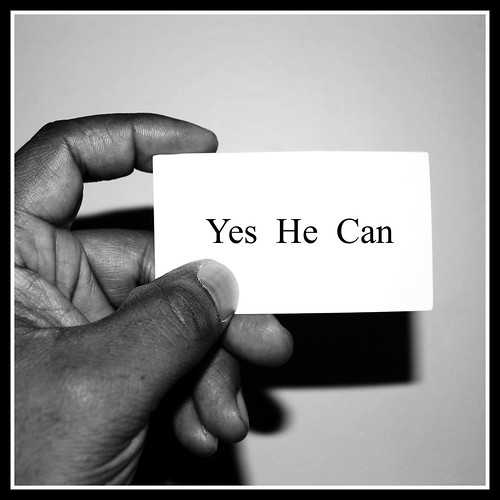

I stood in the kitchen very early this morning, and turned the radio on. Almost instantly I heard the phrase "President-elect Obama" and felt myself smiling from ear to ear. Jubilation, excitement, relief - but is it a measure of just how wound up we've become about America that I also feel afraid for Obama? Is it just the after-effect of the past eight years, which will melt away in a few days? Will I relax and stop thinking about the possibility of a staring face, a pointed gun, another worldwide scream, a funeral the like of which I hope never to see?

I think so. Hopefully.

America looked at its fears yesterday, and said "Enough". Obama will stride over them, also. He has a lot of work to do. And I am very much looking forward to seeing him do it. Thanks, America. Many, many thanks. :o)

No comments:

Post a Comment